Margaret Atwood wrote, “In the end, we’ll all become stories. Or else we’ll become entities. Maybe it’s the same.” The profundity in the quote can be accessed in various layers and perhaps countless contexts, if the path to accession is clear and objective. As educators we weave stories, multiple ones, often a singular time as we walk into the classroom to teach and learn with our students. We do hope that our students achieve success (however subjective that word is) and significance in life. We wish them happiness and prosperity, but deep down inside we aspire to become stories in their lives. There lies a possible sense of actualisation for a profession that is still not viewed through the deserved lens of reverence in our society. In concert with that lies the method, the pedagogical practices, the struggle between the established conventions and the effervescent demands of a new time. When machines are getting better every second to write stories, can we essentially become the important characters in our students’ stories? The question can be spirally assessed from understanding why story-telling as an art form must be incorporated in everyday pedagogical practices, irrespective of grades, subjects and examination boards.

Grace M Deniston-Trochta in her article, “The Meaning of Storytelling as Pedagogy”, claims storytelling as a transformative educational practice—one that leverages narrative to connect academic content with students’ experiences (direct or indirect), deepen engagement, exercises empathy and animate learning through emotional and imaginative resonance. C. Abrahamson’s 1998 article “Storytelling as a Pedagogical Tool in Higher Education” also emphasises storytelling as one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring methods of teaching, predating writing itself. The paper traces how, from ancient times, stories were used to explain life, transmit cultural values, preserve history, and ensure continuity across generations. Abrahamson argues that storytelling is not only a historical tool but also a powerful contemporary pedagogical strategy in higher education that can engage learners emotionally and cognitively and has the ability to contextualise abstract concepts. The ancient traditions of Panchatantra, Jataka and many more that sprung and sustained in our country’s cultural identity are burning examples of the potency of the form.

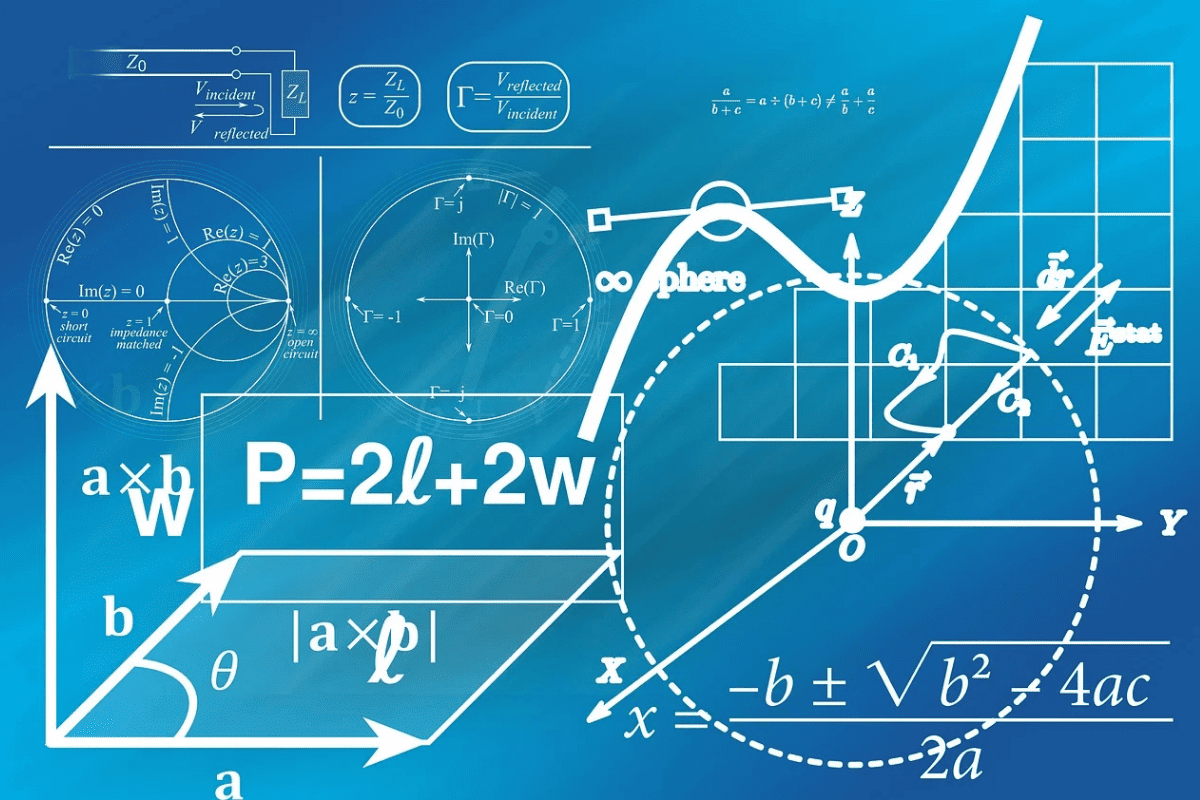

The question hence transforms from ‘can we’ to ‘how can we’ in the context of our daily teaching-learning process. The curricula and the consequent syllabi cannot avoid including a series of topics and concepts that appear to demand a didactic form of transference. Learning facts, keeping track of (memorising) events and causality, derivation of mathematical steps, practising drills to develop a particular skill all of these are fundamental routines in a students’ daily learning cycle. Perhaps no one could deny that any education system is not afflicted by the mundane, but if we plan, design and execute these monotonous practices through stories, it might help the students see beyond their obvious disenchantment with the mounting content.

The stories of the first cartographers, or the ones who risked their lives just to draw a simple map for the later folks to follow could help students empathise with the skill of drawing a map. The stories of how a scientist thought through all logical possibilities, threw away his old ideas and jumped into some new light, stood at the desk for long hours in a day to derive a simple equation (Max Planck did that) could help students understand the rigour of going through such an arduous process. There are several stories (might be concocted at various cultural epochs) that has led to usage of certain words which are not parliamentary in school premises and yet students use them and get in trouble. A teacher can definitely try and invoke a conversation in the class to create a shared understanding of those words through those stories and perhaps allay the unnecessary taboo attached to such actions. There are several academic disciplines which are taught through stories and there are others where finding a contextual story could be challenging. For example in a class of Accountancy, where students are expected to do long structured sums, while deciphering the meanings of debit, credit etc., the funny anecdote of Stephen Leacock and his ordeal while opening an account in a bank could bring a different perspective to the learning. Another example could be of “An Account of Capers” by Bruce Marshall (1988) chronicles the life of an accountant whose otherwise efficient practices somehow land him in intriguing political and espionage entanglement.

The fascinating story of one physicist and a zoologist Francis Crick and James Watson, working together to give us the first structures of DNA has the potential to make students realise that biology is not a collection of mindlessly memorisable concepts, but a map of logical findings. The idea of the disparity of power in the workplace, especially in science can be layered down to the students through the dismal stories of Dr. Subhah Mukhopadhyay (India’s first exponent of IVF) or Sophie Germain, who had to take a male pseudonym to make the contemporary community take her works in mathematics seriously. Resilience in life cannot be taught but the stories of academicians, or other successful performers can be used creatively to make students aware of the power in grit, practice and relentless focus.

The examples mentioned above are just a few drops where the ocean of stories stays at our disposal. The seamless weaving of those stories in a lesson plan rests with the teacher. The usability, perspective and contextualisation of such stories demand reflection and thoughtfulness from the teachers. At the end we must remain aware that the students are going to create and live their own stories, but can we give them a framework to start writing their own? Can we bring to them the countless instances of human experience that have shaped our lives that we live now? Can we help them reflect on the recurring values and vices of the human species so that they can learn those apparently dull topics, not in a formulaic manner but with some humanitarian stances? I think we can, if we plan well, read more and believe in the stories that made us who we are.

Originally Posted on- https://stepbystep.school/blog/lesson-plans-and-story-telling/

Write a comment ...